|

|

Over the last year, many U.S. Naval Personnel have

written to the Gyrodyne Helicopter Historical

Foundation, submitting

quite a few stories of their DASH experiences; some funny and some not. If

you have a story, please submit pictures with it, as well as your name,

ship name and date of experience. We'll try to post those stories as they

come in. Thanks for your help!

|

|

The Crew of the USS Anderson (DD-786) enjoy the

traditional cake (above) following the 100th landing of their QH-50C DASH

on-board (seen right).

Taken in the Gulf of Tonkin, August 1964 |

|

How former CNO Admiral Arleigh A. Burke USN, came to visit the U.S.S.

Anderson (DD-786) on Labor Day Weekend, 1962. By VADM Emmett Tidd

USN (Ret).

|

" The Admiral was aboard, having accepted my invitation. When I

informed the ComCruDesPac staff a few days before the visit, that he would

be coming aboard, they were in a snit about my going over their heads with

such an invitation. I explained (to little avail) that the invitation had

been extended before I detached from OpNav, after a tour working under

Admiral Burke while he was still CNO, and I was way down the ladder in his

Strategic Plans Division, but briefed him frequently on force level

objective plans. He had been retired only a very few months before that

visit, but had frequently expressed a continuing interest in

"HIS" FRAM I & II conversions, and the DASH and ASROC

programs. When I received my orders to RBA (Naval Destroyer Richard B.

Anderson), still in conversion at Bremerton, I mentioned it in a call on

him. He urged me to keep him informed when we would be back in commission

and available for a visit.

" The Admiral was aboard, having accepted my invitation. When I

informed the ComCruDesPac staff a few days before the visit, that he would

be coming aboard, they were in a snit about my going over their heads with

such an invitation. I explained (to little avail) that the invitation had

been extended before I detached from OpNav, after a tour working under

Admiral Burke while he was still CNO, and I was way down the ladder in his

Strategic Plans Division, but briefed him frequently on force level

objective plans. He had been retired only a very few months before that

visit, but had frequently expressed a continuing interest in

"HIS" FRAM I & II conversions, and the DASH and ASROC

programs. When I received my orders to RBA (Naval Destroyer Richard B.

Anderson), still in conversion at Bremerton, I mentioned it in a call on

him. He urged me to keep him informed when we would be back in commission

and available for a visit.

After RBA's shakedown and

refresher training and other operations, when I was notified of dates that

we would be one of

the Open House ships for visitation, I also heard that Admiral Burke was

to be in town during that period. I quickly sent off an invitation to the

Admiral. I also asked the wardroom and Chief Petty Officers to brainstorm

what we could do to make our Open House something special. They must have

been getting used to such requests from me by then, for almost immediately

the Sonar and ASW gang came up with ideas. One of the best came from Chief

White and possibly Chief Sonarman Zech. They had contacted an old shipmate

on the DASH project to get us a prototype DASH on board. I don't know in

pounds of coffee just how much it must have cost us, trading with those

poor deprived shore based technicians. No ship in San Diego at that time

could boast of having had a DASH on board. But, as we tied up at Broadway

Pier, there was a crane standing by to load one on board RBA! (The crane

was also probably needed to off load from RBA their pallet of coffee!) would be one of

the Open House ships for visitation, I also heard that Admiral Burke was

to be in town during that period. I quickly sent off an invitation to the

Admiral. I also asked the wardroom and Chief Petty Officers to brainstorm

what we could do to make our Open House something special. They must have

been getting used to such requests from me by then, for almost immediately

the Sonar and ASW gang came up with ideas. One of the best came from Chief

White and possibly Chief Sonarman Zech. They had contacted an old shipmate

on the DASH project to get us a prototype DASH on board. I don't know in

pounds of coffee just how much it must have cost us, trading with those

poor deprived shore based technicians. No ship in San Diego at that time

could boast of having had a DASH on board. But, as we tied up at Broadway

Pier, there was a crane standing by to load one on board RBA! (The crane

was also probably needed to off load from RBA their pallet of coffee!)

Of course, it was a

minor matter that we had not been certified to operate a DASH, much less

that we also lacked having the instrumentation required for such

operation. But, we weren't saying it was "operational" -- just

that it was the first FRAM-I to have a DASH "on board"! OK?

A few days earlier I received the visit acceptance from Admiral Burke, and

on the same day I received a verbal reprimand that (I was told) came from

the ComCruDesPac Chief of Staff, when he had been advised by Admiral Burke

that he wanted to visit (specifically) RBA during his coming visit with

Rear Admiral Virden, then ComCruDesPac. Of course, as soon as I received

Admiral Burke's acceptance, I also invited everyone up my chain of

command. My Squadron and Flotilla commanders took it in stride, and seemed

pleased that we could show Admiral Burke examples of what he had

personally worked so hard to get into the fleet. That was the same

frequency that I was on. But, as Admiral Ike Kidd used to say, "My

Ox was already in the ditch." As far as the CCDP Chief of Staff

was concerned, Emmett Tidd had fouled up their whole visit schedule.

Later, in private, I apologized to Admiral Burke, hoping I had not

embarrassed him with complicating his ComCruDesPac visit.

He roared with

laughter, and said, he always expected his destroyer skippers to get bumps

on more than just their shins -- that a skipper doing something for his

crew sometimes resulted in getting a thump on the head, but that was not

all bad. And I did survive, after all ! He roared with

laughter, and said, he always expected his destroyer skippers to get bumps

on more than just their shins -- that a skipper doing something for his

crew sometimes resulted in getting a thump on the head, but that was not

all bad. And I did survive, after all !

To have been associated with Admirals Burke and Wendt, was a grand treat

for me, and for our crew. But, serving with my RBA crew was every bit as

grand, and an honor. They were worth all the bumps I could possibly garner

on my head."

Former 3-Term Chief of Naval

Operations, Admiral Arleigh A. Burke (in suit) aboard the Navy destroyer

U.S.S. Anderson (DD-786) at San Diego, California, upon the introduction

of the DASH Weapon System to the Pacific Fleet and celebrating the

Sixtieth Anniversary of Destroyers in the U.S. Navy; Labor Day Weekend,

1962. Pictured with the Admiral (both photo's),

from left, CPO White, NAMTG, DASH Unit, San Diego; Cdr. Tidd, C.O. USS

Anderson; Adm Burke; Rear Admiral Wendt, Destroyer Flotilla Commander (bottom

photo only).

|

The Installation of DASH in Yokosuka, Japan

|

The small two story building on the extreme

right was the building the Gyrodyne representatives (called Techreps)

operated out for our first three or four years in Japan (MOTU 7). The two

FRAM destroyers on the far right did not yet have their drones. The first

DASH equipped ships did not get to Yokosuka until the fall of 1963.

Captain Robert H. Beyer USN (ret)

Left to right, USS John S. McCain DLG-3, undetermined

target, USS Prairie AD-15 (DASH Tender), USS Coontz DLG-9, USS Wedderburn

DD-684., USS Duncan DD-874, and USS De Haven DD-727

|

|

Some Personal Stories........

|

My name

is Marion Price, Capt. USNR-Ret. When I was on active duty ('64-'68) my

friends called me buz.

The reason I was searching the

Internet is this: The Navy (in cooperation with Gyrodyne) picked my ship,

USS Corry, DD-817, in early 1966 to be the "star" ship with its

DASH system for the Navy's new training film in DASH operations. Since I

was featured in this film as one of the controllers, I

was trying to locate a copy so my children could see what "daddy did

in the war." Mainly as a keepsake. By the way... you guys

wouldn't happen to have a copy of that film would you?

After I left active duty in the Navy, I went on to serve in

the Naval Reserve ( Intelligence) for several years and recently retired.

I am vice president of an advertising agency in Dallas, Texas.

I must say... when I saw the photos on your site, my eyes got a bit misty.

Thanks for keeping the dream alive... this system makes a lot of

sense...

even more so today!

Sincerely, M. S. "Buz" Price,

|

|

My

name is Joel Labow and I went through DASH training at Dam Neck, Va. in

December 1967 and then was ASW officer and senior DASH controller on USS

McCloy (DE-1038) from 1967 to 1969.

My

name is Joel Labow and I went through DASH training at Dam Neck, Va. in

December 1967 and then was ASW officer and senior DASH controller on USS

McCloy (DE-1038) from 1967 to 1969.

McCloy was one of a semi-experimental

class of DEs that mounted a SQS-26 (AXR) sonar and bow-mounted ASROC (with

no magazine for reloads). IMHO to the end of the DASH era she and her

sister Bronstein were the only 2 ships that had the capability to make

full use of the system's full range capability. Under ideal sonar

conditions we once ran a successful attack with a MK 46 exercise torpedo

at 19,500 yards. Of course we also lost one very publicly on a UNITAS

cruise!

Bronstein and McCloy were equipped with the original

SQS-26 when they were commissioned in 1963 and in fact were purpose-built

to be test beds for the installation. They represented a halfway step

between the small Dealey class and the larger Garcias. They incorporated

the same 600 PSI engineering plant as the Dealeys, but interestingly even

though they were considerably larger they were faster as well, probably

because the large bow-mounted sonar gave them a more efficient hull form.

The original

systems were miserably unreliable and the SQS-26 AX installed in the

Garcias wasn't much better. When I joined McCloy in the summer of 1967 she

was in the yard getting the SQS-26 AX (major retrofit).....both she and

her sister went straight from SQS-26 to SQS-26 AX(R) without getting the

AX. This system was more reliable, but the Bronstein class was really too

small for this sonar.....the equipment rooms filled the entire forward 1/3

of the ship and we couldn't fire our forward 3"/50 mount without

dropping the sonar off the line! Bronstein and McCloy were equipped with the original

SQS-26 when they were commissioned in 1963 and in fact were purpose-built

to be test beds for the installation. They represented a halfway step

between the small Dealey class and the larger Garcias. They incorporated

the same 600 PSI engineering plant as the Dealeys, but interestingly even

though they were considerably larger they were faster as well, probably

because the large bow-mounted sonar gave them a more efficient hull form.

The original

systems were miserably unreliable and the SQS-26 AX installed in the

Garcias wasn't much better. When I joined McCloy in the summer of 1967 she

was in the yard getting the SQS-26 AX (major retrofit).....both she and

her sister went straight from SQS-26 to SQS-26 AX(R) without getting the

AX. This system was more reliable, but the Bronstein class was really too

small for this sonar.....the equipment rooms filled the entire forward 1/3

of the ship and we couldn't fire our forward 3"/50 mount without

dropping the sonar off the line!

The preceding top of the line system was the SQS-23, but I

don't think the SQS-26 evolved from the -23.....it was a completely new design to take advantage of bottom-bounce and convergence zone modes.

My favorite DASH 'war story'

took place on our 1969 UNITAS cruise. At that point the Navy was trying to sell the plans of the Bronstein class

to the Brazilians and so we were crawling with high-ranking BN officers. Wouldn't you know it.....our deck control box died just before a

demonstration night flight. Fortunately we were in company with a FRAM I and promptly got her to highline her box to us. By then it was almost

completely dark when I was doing my preflight check, and I couldn't really

see how the rotors were responding to the stick movements. As you have probably figured out by now.....the other ship's system was wired 180

degrees out from McCloy's, so when I launched the drone it did a '180' about 3" off the deck!

The emergency procedure for this is to

disconnect the box from the ship's gyro, then put the drone in cruise mode and

reverse the heading by 180 degrees, then resume stick control and land.

Fortunately this worked like a charm and we were able to pretend to the Brazilian

admirals that this was a 'routine nighttime touch-and-go! I then proceeded

to my stateroom and shook for several hours! As you can see the episode made

a lasting impression since I still remember it clearly even though it was almost 32 years ago! BTW the Brazilians decided not to buy the

plans.....but hopefully not on the basis of our DASH misadventure. gyro, then put the drone in cruise mode and

reverse the heading by 180 degrees, then resume stick control and land.

Fortunately this worked like a charm and we were able to pretend to the Brazilian

admirals that this was a 'routine nighttime touch-and-go! I then proceeded

to my stateroom and shook for several hours! As you can see the episode made

a lasting impression since I still remember it clearly even though it was almost 32 years ago! BTW the Brazilians decided not to buy the

plans.....but hopefully not on the basis of our DASH misadventure.

After 5+ years as a DD/DE sailor I transferred to the Medical Corps and am about to retire with 35+ years service.

Best regards,

Joel Labow, CAPT, MC, USN

|

|

|

I taught the electronics maintenance to five (I think), JMSDF officers.

The last I knew the JMSDF had only 10 QH-50's, and logged more time in the

air than the USN with its hundreds. The last I knew the JMSDF had

not lost a drone. Several years ago a DASH equipped JMSDF ship

visited San Diego, and I was able to go to the DASH hangar to see how they

did it. :-)

I taught the electronics maintenance to five (I think), JMSDF officers.

The last I knew the JMSDF had only 10 QH-50's, and logged more time in the

air than the USN with its hundreds. The last I knew the JMSDF had

not lost a drone. Several years ago a DASH equipped JMSDF ship

visited San Diego, and I was able to go to the DASH hangar to see how they

did it. :-)

Although I never saw a Snoopy version, I did have a couple of

students who went to that program. I did see some video taken by

Snoopy in Vietnam.

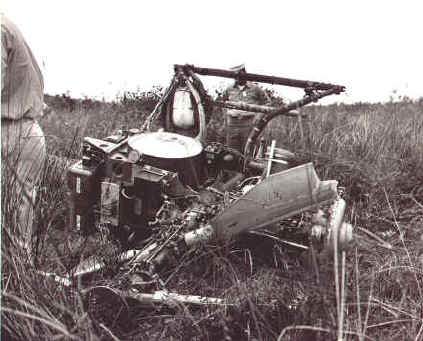

As I recall, the early QH-50D's crashed because of a missing

oil path in the transmission; the rotor mast would snap off after running

for a few minutes!

Flying a QH-50C/D from San Clemente Island to the ships was

interesting. The unmodified drones had an altitude range of +1000 to -200

feet from the launch altitude. The launch site on San Clemente is

more than 200 feet above sea level. Prior to launch, the drone was

made to think it was at about +750 feet. This was done by connecting

the altimeter test set to the drone's altimeter, and setting the test set

to +750 feet.

Good old days.

Cecil Houk, ET1 USN Ret., AG6I

|

|

|

I was one of the first LANTFLT Navy trained Dash Controllers. My

training began at Utility Squadron 6 (VU-6) at Norfolk, VA in November

1962 and was completed in the spring of 1963. I then took my

detachment onboard USS J.C. OWENS (DD-776). The birds were grounded

during my short assignment on Owens while the problems with the

Electro-Mechanical Rotary Actuator were researched. I spent a month

or so at Pax River putting hours on the aircraft during this time. I

left the program in June of '63 to attend Destroyer School and never

served on a DASH ship again. I was involved in discussions at

COMCRUDESPAC in 1966 concerning the gunfire spotting role and saw some

video materials taken from the tests.

I was one of the first LANTFLT Navy trained Dash Controllers. My

training began at Utility Squadron 6 (VU-6) at Norfolk, VA in November

1962 and was completed in the spring of 1963. I then took my

detachment onboard USS J.C. OWENS (DD-776). The birds were grounded

during my short assignment on Owens while the problems with the

Electro-Mechanical Rotary Actuator were researched. I spent a month

or so at Pax River putting hours on the aircraft during this time. I

left the program in June of '63 to attend Destroyer School and never

served on a DASH ship again. I was involved in discussions at

COMCRUDESPAC in 1966 concerning the gunfire spotting role and saw some

video materials taken from the tests.

I now live in San Diego.

C. F. Bigsby, Capt USNR-Ret

|

|

From the Gyrodyne Helicopter Historical Archives,

written over 36 years ago, by

DASH Officer Lt. Jg Jerome M. Kopel, USN, of the USS VAN VOORHIS:

"USS

VAN VOORHIS, 29 September 1965: QH-50C DS-1281 was being flown with

weapons this day with takeoff normal with CIC taking control and flying

DS-1281 to 340 degrees at 5000 yards. At that point the course was

changed to 090 at 80 knots true airspeed. At 1651, an eyewitness

reported a puff of white smoke (flame out) and 1281 crashed into the

sea. The ship headed for the crash point with both oil and JP-5 seen

bubbling up to the surface. It is theorized that the flotation gear did

not work due to the exploding of the two MK 64 Mod SUS bombs which were

attached to the drone at the time of the accident. Cause of accident was

engine failure."

Now, to aid in our quest for

education, we asked two experts to explain what was a MK64 MOD SUS Bomb

was....and the explanation was stated as:

From CAPT Nelson Jackson, USN

(Ret.), CO RUPERTUS (DD-851) AUG ' 69 - JUL ' 71:

SUS

are low level explosive devices, about the size of a hand grenade but

much, much less explosive energy, which are used/detonated when working

against submarines in ASW training. They were developed and employed

to imitate an actual explosion when the destroyer/aircraft

"fired" at a sub contact. Previously, there were just

audio signals and frequently arguments "I got you!"/"No you

didn't!". SUS brought more realism into the game and minimized

the arguments.

From Wallace (Dusty) Rhodes (our

munitions expert!), Retired, Master Chief Torpedoman's Mate (TMCM):

SUS is Sound Underwater

Source or Sound Underwater Signal (I've heard them referred to by both terms over the last 38 years).

The SUS charges were used by

ships and aircraft, when non verbal (UQC/WQC) communications with a

submarine were inappropriate. These units

hold enough explosive to wreak havoc with equipment, but I don't remember where

their stores stations were on the DASH. From

Gyrodyne Helicopter Historical Foundation:

We don't know where the

MK 64's were loaded either...not a single picture or manual reference to

such an installation! |

|

Did you know that the Cruiser, USS BELKNAP (DLG-26) was

equipped with DASH?

I read your letter, with interest, in The Ping

Jockey about the DASH program. I am retired ST (E8) and was a 26 AXR sonar

tech and

instructor at FSS in Key West. Taught 26 AXR Maintenance from

1966-1969.

Before then I received GE training on the 26AX prior to it being retrofitted, I

was a member of the BELKNAP (DLG-26) pre-commissioning crew as an ST1 (E6 pay grade)

in Bath

Iron Works Sep '64 and served until May '66. The BELKNAP entered

Norfolk Naval Shipyard in early December 1965 for a month upgrade period

to be fitted with the DASH system. On January 11, 1966, BELKNAP

departed D & S Piers for three days of DASH Ship Qualification Trials

with a FRAM (?) Destroyer already DASH qualified. The BELKNAP, to my

knowledge, successfully operated the DASH System and handed off the Bird

with the other ship.

Before then I received GE training on the 26AX prior to it being retrofitted, I

was a member of the BELKNAP (DLG-26) pre-commissioning crew as an ST1 (E6 pay grade)

in Bath

Iron Works Sep '64 and served until May '66. The BELKNAP entered

Norfolk Naval Shipyard in early December 1965 for a month upgrade period

to be fitted with the DASH system. On January 11, 1966, BELKNAP

departed D & S Piers for three days of DASH Ship Qualification Trials

with a FRAM (?) Destroyer already DASH qualified. The BELKNAP, to my

knowledge, successfully operated the DASH System and handed off the Bird

with the other ship.

When the BELKNAP returned to the Norfolk D&S

Piers the word was

passed for Liberty Call with the exception of Supply, the DASH Det group

and AS Division. I inquired to the reason that liberty was on hold

and learned from the Sonar Maintenance Officer ENS. Ross Cameron that the

DASH System was scratched from installation on the BELKNAP Class ship.

We off-loaded every thing associated with DASH. The reason given was

that the authorities in Washington decided to configure these ships with a

manned aircraft.

This ended my association with DASH. I

never saw DASH after that. In 1969 I returned to sea on USS EDWARD

MCDONNELL (DE 1043) (in '75 re-designated FF 1043) and the only remnants

was the control station outside the DASH Hanger that most ships converted

to a Quarterdeck Shack. In the early 1970s, the GARCIA Class Fast Frigates

(FF 1040, 1041, 1043 through 1051), the KNOX Class Fast Frigates (FF 1052

- FF 1097) and the BELKNAP Class (CG 26 through CG 34) were fitted with

LAMPS I capabilities including the new telescoping hangar

KEN WRAY

BAE SYSTEMS, WASHINGTON, DC

AN/SQQ-89(V)2/7/8/10/12/14 & AN/SQS-53D(V)

|

|

The Issue of DASH Reliability related to DASH hours

actually flown

"Ken Wray has been passing to me some of

your mail concerning the demise of the DASH Weapon system. Ken and I were

consultants for NAVSEA Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) Systems for 12-15

years in which we interfaced on various programs and are very good

friends.

I am a retired Navy Line Captain and was the

Force ASW Officer/Air Officer for COMCRUDESLANT in Newport from

Approximately 1967-1969. During that period DASH was running into problems

mainly because of a few accidents and the fact that DASH was not meeting

the reliability standard of a loss for every 100 hours of operation. Most

of the problem was that ships WERE NOT FLYING DASH on a regular program

and as a consequence, pride and maintenance fell off. We instituted a

program that required all DASH ships to fly 4 hours a month. Pretty soon

there started a competition to see who could fly the most hours. One ship,

I believe the STEINAKER, kept a DASH in the air for over 24 hours. Pretty

soon reliability improved to something like 360 hours of operation for

every loss, and torpedo hit percentage with DASH rose into the 90

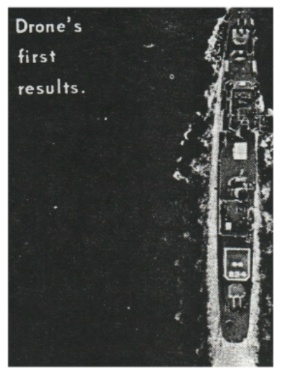

percentile.

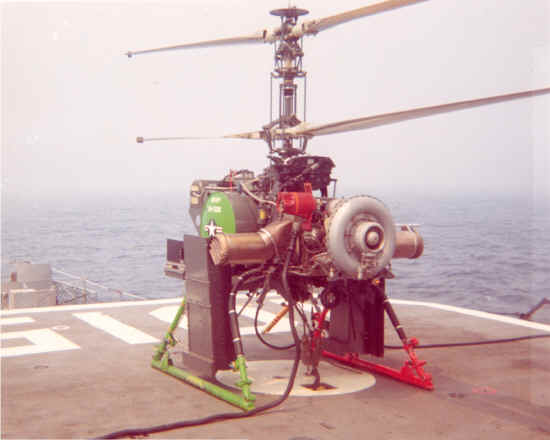

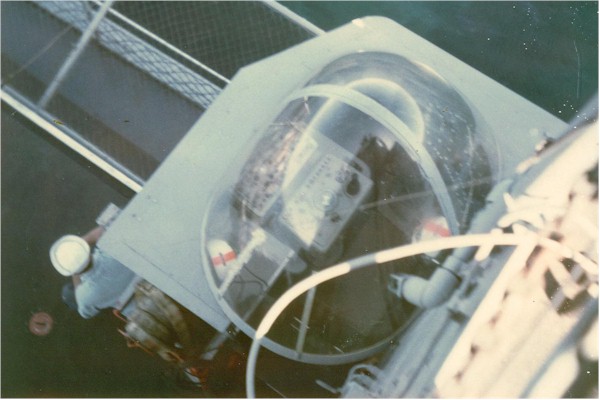

We also did an ASW test using the HAMMERBURG

(DE 1015) using the sonobuoy launcher and monitor developed by Gyrodyne for the Navy (seen right).

We also fitted out extra fuel tanks, transponders, and telemetry for long

distance travel and monitoring. The evaluation results were OUTSTANDING

with the DASH operating out to 72,000 yards and monitoring the sonobuoys

with 92% detection and tracking. I remember one item in the report that

stated that the DASH was STILL TRACKING a surface ship at 16 miles, as the

DASH was LANDING on HAMMERBURG. I relayed this evaluation--even though the

numerics may be something different--because OPTEVFOR did not press on

with it.

developed by Gyrodyne for the Navy (seen right).

We also fitted out extra fuel tanks, transponders, and telemetry for long

distance travel and monitoring. The evaluation results were OUTSTANDING

with the DASH operating out to 72,000 yards and monitoring the sonobuoys

with 92% detection and tracking. I remember one item in the report that

stated that the DASH was STILL TRACKING a surface ship at 16 miles, as the

DASH was LANDING on HAMMERBURG. I relayed this evaluation--even though the

numerics may be something different--because OPTEVFOR did not press on

with it.

I would also pass to you that we sent monthly

reports to OPNAV concerning the progress we were making in DASH

reliability and effectiveness. Yet every time I visited OPNAV to discuss

this progress they kept feeding me with data from 1964-1965, which was

poor. It became quite evident that the Navy no longer wanted DASH and

wanted to move onto LAMPS (Light Airborne Multi Purpose System) manned

helicopters.

While COMCRUDESPAC was not into ASW as much

and relied on SNOOPY (reconnaissance version of the QH-50D) more, it was

because that they were primarily engaged in the Vietnam War. However, the

ASW officer at PAC and I had a goal to improve DASH reliability, which we

jointly did.

I remember going to Gyrodyne for Program

meetings and dealing with Mr. Peter J. Papadakos (founder and President of

Gyrodyne). He was a fine man and I still have a few tie pins and a picture

of a DASH that was presented to me by the DASH people at CRUDESLANT. If I

could be of any further help please feel free to ask."

Regards,

CAPT Chris Zirps, USN (Ret.)

|

|

The Issue of PACIFIC Fleet DASH using MK-44 Torpedoes:

From CAPT Nelson Jackson, USN

(Ret.), CO RUPERTUS (DD-851) AUG ' 69 - JUL ' 71:

Back in 1963-1965 when I was the CSO and OPS Officer for DESRON 23 we

did drop some dummy torpedoes from the DASH in ASW training with subs.

I recall at least twice this occurred. The ships in DEDIV 231, out

of Long Beach, at that time, were USS James E. Kyes (DD-787), USS Everett

F. Larson (DD-830)-see right, USS

Walke (DD-723), and USS Frank E. Evans (DD-754). Anyway, we did it.

I never employed torpedoes from DASH on Rupertus, nor do I remember any of

the other Yokosuka DD's ever using torpedoes in training. In fact,

we didn't do much ASW training; it was all Gun Line and chasing the

carriers in Vietnam.

Nelson Jackson.

|

Above, the USS Everett F Larson (DD-830) fires off one

of its' six 5"/38AA guns. Commissioned April 6, 1945 and serving for

30 years, the Larson was subsequently stricken June 2, 1975, sold to South

Korea on October 30, 1972, renamed Jeong Buk and as on 1998, she is still

active in the South Korean Navy. |

|

I came across your web site, and am making this contribution to the

history of the DASH.

I was the Operations Officer on the USS Perkins

(DD-877) from 1962 - 1964. We completed our FRAM II overhaul in late 1962,

and spent the next several months working up towards a planned deployment

in October 1963. We were the second ship in the Pacific Fleet to

receive our DASH. I believe that the USS Buck preceded us by a week

or so. Our DASH s/ns were 1046 and 1057

(perhaps 1059).

LTJG Tom Lynch headed our DASH Detachment. We flew the DASH fairly

often, but as we were often assigned to plane guard duties for days on

end, it was difficult to convince the OTC to let us fly the helo while

flight ops were in progress. Perhaps it was fear of mixing Foxtrot

and Kilo ops!

LTJG Tom Lynch headed our DASH Detachment. We flew the DASH fairly

often, but as we were often assigned to plane guard duties for days on

end, it was difficult to convince the OTC to let us fly the helo while

flight ops were in progress. Perhaps it was fear of mixing Foxtrot

and Kilo ops!

We did have one exciting evolution, however. In

June of 1963, President Kennedy visited the First Fleet, and VADM Ramage

had the force preparing and rehearsing for days in preparation for the

at-sea Naval Review. Perkins' role was to make a high speed pass up

through the formation with

our DASH in the air. On the day of the performance, we (and the

entire force) acquitted ourselves admirably, and the entire demonstration

went off without a hitch.

Perkins was the first ship to deploy to WESTPAC with

the DASH. Throughout our 6-month deployment we flew

"regularly", but as with our EASTPAC operations, there always

seemed to be the problem of interference with what the Task Group was

doing.

We did not lose either of our birds, and we always read carefully the

SITREPS and Damage Reports that were issued regarding damage or loss to

the DASH's.

CAPT Albert A. Nannini, USNR, Ret.

|

|

My son is trying to get me in trouble with the DASH people. Actually

I have little to contribute. I had command of PERRY (DD-844) late in

her life. She was the first FRAM I destroyer and I had command when she

was a little long in the tooth. These ships were modernized to

extend their lives 8 years and I had the ship at the start of the second 8

years. After I took command we only flew the DASH once as the system

was being removed from the ships about that time and we were getting ready

to deploy to WESTPAC. It was flown successfully but I must confess

that during the flight I could visualize the DASH flying into the after

stack and I really wasn't unhappy to see it go. I had heard lots of

horror stories. I felt at the time that success with DASH would depend on

a maintenance crew that really took and interest in the birds and just

didn't do the perfunctory maintenance. That plus actually flying

them as much as possible. Since PERRY was named for both Oliver and

Mathew Perry the crew named the two birds "Ollie and Mattie." I

think that PERRY had had a pretty good record with the DASH up to that

point.

My son is trying to get me in trouble with the DASH people. Actually

I have little to contribute. I had command of PERRY (DD-844) late in

her life. She was the first FRAM I destroyer and I had command when she

was a little long in the tooth. These ships were modernized to

extend their lives 8 years and I had the ship at the start of the second 8

years. After I took command we only flew the DASH once as the system

was being removed from the ships about that time and we were getting ready

to deploy to WESTPAC. It was flown successfully but I must confess

that during the flight I could visualize the DASH flying into the after

stack and I really wasn't unhappy to see it go. I had heard lots of

horror stories. I felt at the time that success with DASH would depend on

a maintenance crew that really took and interest in the birds and just

didn't do the perfunctory maintenance. That plus actually flying

them as much as possible. Since PERRY was named for both Oliver and

Mathew Perry the crew named the two birds "Ollie and Mattie." I

think that PERRY had had a pretty good record with the DASH up to that

point.

I'm not the one to nominate PERRY for the DASH Wall of

Honor, that should come from previous crew members. If I get any

info on the history of the PERRY with DASH at the next ships reunion I'll

send it along to you.

I have built a model of PERRY as a FRAM I and have been intending to build

a DASH model for the flight deck.

Capt. Peter J. Watson, USN, Retired

|

|

I only recently found your website about the DASH helicopters and was glad

to see a website on what I always considered to be a great aircraft.

My name is Alan R. Westfall, CAPT, USNR-Ret, and I was a DASH Officer on

the USS MOALE (DD-693) from Dec. '65 - Feb. '68. The CO of the ship

liked the DASH because we did not have the ASROC weapon system. DASH

was our best ASW weapon and the CO used it as much as possible.

I only recently found your website about the DASH helicopters and was glad

to see a website on what I always considered to be a great aircraft.

My name is Alan R. Westfall, CAPT, USNR-Ret, and I was a DASH Officer on

the USS MOALE (DD-693) from Dec. '65 - Feb. '68. The CO of the ship

liked the DASH because we did not have the ASROC weapon system. DASH

was our best ASW weapon and the CO used it as much as possible.

I wanted to share with you an event in which we

participated in July, 1967. Our squadron was DESRON 10. The squadron

was returning from a 6 month Med Cruise and my CO wanted to do something

with the helicopters on route home. I outlined a plan to have a DASH

helicopter in the air continuously for 48 hours.

The plan was based on a schedule that would rotate the flying

duty to each ship. The flight would be for one hour with a five minute

overlap for next flight. We used four destroyers (Moale, Rush, Roan,

Lloyd Thomas). Each ship had two qualified DASH Operators so they

could rotate flying the A/C.

The routine was:

1. Fly one hour

2. Rest two hours

3. Stand-by one hour (in case the scheduled ship could not lift-off)

4. Fly again.

The exercise worked very well. All ships flew their

scheduled time and we kept a DASH in the air continuously for 48 hours.

Later in the year the MOALE received the Atlantic Fleet ASW Award for

outstanding ASW performance and the 48 hour Dash exercise was a

significant factor in winning that Award.

I loved flying the DASH Aircraft. We had a good maintenance

crew and flew whenever we could. The only problems we had were with

the radio control and guidance systems. If we had had today's

digital systems, we would have been able to tell the Navy to keep their

manned helicopters on the big ships. The airframe always performed as

expected.

I have always felt the DASH was a good transition system for

the manned helicopters that finally did deploy on the destroyers. It

got the "black shoes" used to having aircraft on board.

Thank you for letting me share this experience with you. I

know there are many old sailors like me who had a good experience with

your aircraft.

Alan R. Westfall

CAPT USNR-Ret

Houston, Texas

|

|

My name is Tom Lynch and

my involvement in the DASH program began in mid 1962. Here are some of the

details I remember, although the years may have dulled what were once

crisp and exciting memories.

I was selected as one of

the original people to set up the Fleet Introduction Site on San Clemente

Island, California. Others included Lt. Pete Lostrico, Ltjg's El

Chenoweth, Norm Andersen, Charlie Cook, Nick Ide and Jim Prather. We

were all assigned to Utility Squadron 3 at NAS North Island CA. We were

trained at the Gyrodyne Plant, St James, Long Island, NY. Some of us also

got some "stick time" at Pax River Naval Air Test Station. I

later served as the original DASH Officer aboard USS Perkins (DD 877), the

first DD to take the DASH to WESTPAC.

WESTPAC.

My detachment consisted

of Barringer, EM1; DeAcosta ET2; Goblirsch, AT1 and West, ADJ2. We flew

the QH50C and I believe our "bird" numbers were DS 1036 and DS

1047! We also used the DASH to transport critical spare parts (and

movies) between Perkins and other DASH equipped ships. A

few years after leaving Perkins, I was interviewed (1965 or 66 ?) in San

Diego by Hugh Downs, host of the old "Today " show. We did a

very brief segment on what DASH was, its mission, capabilities, etc.

As I recall, a

DASH equipped DD steamed very, very close to the beach, launched their

DASH and flew it within 200 yards of the city of San Diego to ensure the

TV people got good close-ups!!

I hope this helps and please let me know if I can be of any further

assistance.

Take Care

Tom Lynch

Lt, USN-Ret

|

|

|

|

It was 1969 and I was a Naval Reserve in

Reading

PA

and it was time to go active for two years.

I received my active duty orders for Duty:

shore at LANTFLTUSNAVDASHTRAUDAMNECK. I

had

no Idea what these letters meant.

I drove from

Reading

to Dam Neck and discovered this duty was not going to be so bad.

Living in VA Beach was not too hard to take. Also, during my active

duty was the era of the “Z grams”.

The “Z grams” allowed; long hair, not having to wear dress

uniforms to drive home from base, beards and side-burns were allowed. no Idea what these letters meant.

I drove from

Reading

to Dam Neck and discovered this duty was not going to be so bad.

Living in VA Beach was not too hard to take. Also, during my active

duty was the era of the “Z grams”.

The “Z grams” allowed; long hair, not having to wear dress

uniforms to drive home from base, beards and side-burns were allowed.

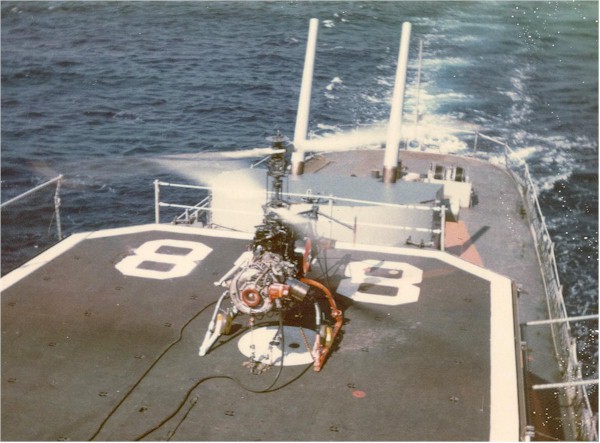

Attached are two pictures

taken at DASH Training Unit, Dam Neck about 1970.

I was at Dam Neck from about ’70 till closing.

I was an Electronics Technician Third Class, USNR. I was mainly

responsible for all the airborne TV cameras and transmitters, as well as

all the TV ground receiving equipment.

We did seem to have a lot of

crashes at Dam Neck. We

dropped a lot of birds in the water. There were quite a few crashes while

I was there, I do remember that the inflation device and strobe never

worked when dropped in the water. We had to send in divers to locate

the remains. I also remember flying two birds at one

time and both went into the water. One

of the birds was carrying a payload from NRL.

This was towards the end of DASH Dam Neck, and I think the NRL pod

was to make the bird look like a ship – to an oncoming missile.

NRL was not very happy about our little failure.

Toward

the end of DASH Dam Neck I also worked on CNO Project DS555. This was to

use the birds a radio relay for amphibious landings. Toward

the end of DASH Dam Neck I also worked on CNO Project DS555. This was to

use the birds a radio relay for amphibious landings.

Also worked on using

DASH, equipped with a TV camera, to drop small bombs, to disrupt enemy

vehicle traffic.

All programs seemed to go good, except for

the NRL project, but DASH Dam Neck was still closed.

One thing I will never

forget is that while we were at Dam Neck we always went to the base club

for lunch and always had a few beers.

Then get back to work after lunch and get ready to fly a bird.

Sometimes we would have to get under the bird while it was turning,

to check the video transmitter or something.

Of course the rule was to ALWAYS keep one hand on the deck.

Was it the safest thing to do after having a few beers?????

Rick Falkiewicz

Syracuse

,

NY

|

|

|

From: CRUISER-DESTROYERMAN Magazine

- October 1967

"BASILONE Shoots Herself - Using DASH to carry Camera"

The Newport based destroyer BASILONE , presently on duty

with

the

Sixth Fleet, has the

Sixth Fleet, has

accomplished what is believed to be a photographic first.

At the same time she has opened a new variety of possible uses for the DASH

[Drone Anti-Submarine Helicopter] weapons system.

By attaching a camera to the underside of the drone helicopter and rigging

the shutter release to the weapons drop switch, BASILONE 's DASH controller

positioned the drone over the ship and snapped a series of pictures.

Using a Polaroid Land Camera, the controller was able to return the drone

and the camera to the ship after each picture and check the results, with

refinements being made after each shot.

The camera was mounted in a variety of angles in order to get side views, as

well as overhead pictures.

BASILONE is now planning to mount a movie camera, and possibly a 35mm

camera, in which the film could be advanced with the drone in the air to

obtain a sequence of pictures.

Now, from the Controller who flew these missions........

I was fascinated, after all these years, to

discover (via Google) so many web sites connected with the former DASH

Weapons System. I was a DASH CIC controller on the USS BASILONE (DD-824)

from July 1966 to September 1967. I attended the DASH Dam Neck school in the

Spring of 1966.

While on a Med Cruise in the summer of 1967, our deck DASH

controller was infatuated with flying as much as we could find time or clear

seas. As noted in the release included in your history section, BASILONE

flew one of its units with a Polaroid camera aimed straight down hooked up

to the bomb release mechanism. We would launch the bird, transfer control to

CIC, and using the sound powered phones, I would be coached by the crew on

the deck into hovering the DASH directly above the ship. When all felt it

was in place, I'd flip the bomb switch and take our picture. We spent hours

launching, transferring control, hovering over the ship, taking the picture,

transferring back to the deck controller, landing, pulling out the picture,

re-cocking the camera, and taking off to repeat the cycle.

We got quite a few pictures with the ship

partially in the picture, but one really good one with the ship fully in the

shot. It may be a little better than the picture included in your history

section printed from the USS BASILONE release. I assume that picture was

from the ones we took, unless BASILONE continued the practice subsequent to

my departure in September 1967.

It was great reading the history of the weapons system. Is there a site for

former DASH controllers? Just curious.

Dave Welsh (formerly USNR LT)

November 2004

|

|

|

I was assigned as Training

Officer at Fleet Composite Squadron 3, Detachment San Clemente Island ( VC-3

Det SCI) from July 1965 to February 1967 training fleet controllers in

DASH. I accumulated over 300 hours as a DASH Controller. We trained twelve

controllers every six weeks. In one class we had 18 students because the

powers that be had scheduled six additional controllers from the Japanese

Naval Self Defense Force.

We developed a standardized curriculum of 30 hours for qualification,

starting with basic maneuver techniques and advancing through cruise

flights, and weapons loads (one dummy MK 44 centerline, two MK 44 dummies

and finally one MK 44 in a side load position. We did deck landings on a

flight deck built next to the control station.

In 1966 Admiral Aurand of the Helicopter wing at Ream Field asked if we

could use the DASH to pick up a downed pilot. As a result we conducted

several test flights to determine if we could carry the weight of a person

hanging below the drone. We found that we could. We also developed the

capability to transfer control of the DASH to a CIC type control station on

board an SH-3A (seen right)

and conducted several test flights while controlling the DASH form the

manned helicopter. We mounted a closed-circuit TV on the drone to enable

the controller in the helicopter to maneuver the drone over a specific

target on the ground.

In 1966 Admiral Aurand of the Helicopter wing at Ream Field asked if we

could use the DASH to pick up a downed pilot. As a result we conducted

several test flights to determine if we could carry the weight of a person

hanging below the drone. We found that we could. We also developed the

capability to transfer control of the DASH to a CIC type control station on

board an SH-3A (seen right)

and conducted several test flights while controlling the DASH form the

manned helicopter. We mounted a closed-circuit TV on the drone to enable

the controller in the helicopter to maneuver the drone over a specific

target on the ground.

We picked up a volunteer form the SEAL Training Base on San Clemente, and

transported him several hundred yards and put him back in the water. As a

final test a fleet unit launched a DASH from a DD, transferred control to

the unit in the SH-3A, transited to San Clemente Island, located and picked

up a dummy, transited back to the vicinity of the DD, and placed the dummy

in the water, where it was picked up by ships boat, and then transferred the

DASH back to the DD where it was successfully recovered.

Admiral Aurand wanted to develop the capability to use DASH to rescue a

pilot downed in North Vietnam, where there was too much risk to insert a

manned helicopter. His only requirement was that all test and development

be done locally so the system could be ready to go with minimum delay due to

test and development.

When the CCTV was mounted we determined that it also had potential for use

in reconnaissance, and for spotting shore bombardment. We launched a DASH

and spotted gunfire during a gunnery exercise at San Clemente Island.

I left the Navy before any of these systems were ready for deployment, and

do not know if they were ever deployed. I seems that this may have been a

precursor to the reconnaissance drones that were used later in Viet Nam.

Raymond H.

Wickman

February 23,

2004

|

|

|

Found you site and loved it. I served on the USS Buck

(DD-761) from 10/68 - 10/71 and the majority of that time served was in the

DASH crew as an ETR2. DASH was inactive when I transferred off but was still

on the ship

and

removed shortly afterwards. and

removed shortly afterwards.

I remember reading the old original DASH logs about testing

etc. right after the FRAM conversion, seems I was told it was early in '62

and was the first west coast DD to get DASH. Things I remember about being

in the DASH crew: Loudspeaker passing the word 'Holiday routine' followed

immediately by 'Flight Quarters', taking control of another ship's DASH helo

for a while, dropping a message on the flight deck of another can that had

just lost their drone by landing it wrong and it rolling across the deck and

off the side when the handling wheels were put on.

Somewhere I also have a 100 hours belt buckle that we

got for flying an almost non-stop 100 hour marathon for some contest or so,

at about 104 hours the aft controller quit. I also remember when the aft

controller's gyro went a little out of spec and the three replacements we

got were all broken, I ended up taking the original apart and bringing it

into +/- 1 degree error after working on it for about a week. On my old

ships jacket I have the DASH patch we had made up, I think I slipped in the

25 hours service bit because of all the flying we were doing at the time.

Our DASH emblem for our ship was a flying grasshopper carrying a torpedo

with it's legs and rotor blades coming out it's back, we had a stencil for

that but it is long gone I think.

Mike Winchester,

July 29, 2004

|

|

|

I told a fellow employee, B-52 driver, that I used to fly a "DASH" He

looked it up on the web and showed me your site.

I was the DASH officer and deck controller on the USS Warrington (DD-843)

based in Newport, RI, from September, 1967, until our regular overhaul in

1969 when the system was off loaded.

Our XO liked to claim records. So, he painted the nose of our DASH blue and

directed me to launch the aircraft before we proceeded north across the

Arctic circle in March/April of 1968 and then land it after we had crossed

the circle. He could then claim that our ship flow DASH across the Arctic

circle.

Our XO liked to claim records. So, he painted the nose of our DASH blue and

directed me to launch the aircraft before we proceeded north across the

Arctic circle in March/April of 1968 and then land it after we had crossed

the circle. He could then claim that our ship flow DASH across the Arctic

circle.

This was true! but I nearly froze in the process.

One other memorable event. I never lost one, but came close. The CO was

standing over my shoulder one day at the deck station as I was doing air

work.

Hovering at about 1000 feet, I started a vertical descent. At about 700

feet, I started cranking in Up collective. But the bird continued down,

almost appearing to accelerate its downward descent. All I could do was

crank in maximum up collective.

Finally, at about 200 feet, I guess it started to find some ground effect

and stopped its descent. The CO smiled and showed his appreciation for my

skillful airmanship demonstration. Little did he know about how much I was

sweating!

He did not realize that until, the drone stopped its descent, I had been

rehearsing in my mind all of the paper work that I was about to have to

complete.

When I returned to CivLant, I earned my airline transport rating and

aircraft mechanics license. I would love to fly the DASH again. If we

could put some cameras and gyro-stabilized sensors on board, I will

volunteer to fly patrol over the Tucson sector for free! In fact, I would

probably pay to do this.

Jim Diehl

May 31, 2005

|

|

|

When I graduated from the U. S. Naval Academy in 1959, I

reported aboard the USS ANTIETAM (CVS-36) as Radio Officer and later, as a

Lt. Jg., became the Assistant Navigator. In June of 1961, I was sent to CIC

Officer/Air Intercept Controller School in Glencoe GA. (Brunswick, GA) and

by January 1962, I had joined the crew of the USS JOSEPH P. KENNEDY JR.

(DD-850), then undergoing FRAM Conversion in the Brooklyn Naval Shipyard. I

became the CIC/ECM Officer and DASH Intercept Controller on the KENNEDY from

FRAM Conversion (spring 1962) until June 1963.

When I graduated from the U. S. Naval Academy in 1959, I

reported aboard the USS ANTIETAM (CVS-36) as Radio Officer and later, as a

Lt. Jg., became the Assistant Navigator. In June of 1961, I was sent to CIC

Officer/Air Intercept Controller School in Glencoe GA. (Brunswick, GA) and

by January 1962, I had joined the crew of the USS JOSEPH P. KENNEDY JR.

(DD-850), then undergoing FRAM Conversion in the Brooklyn Naval Shipyard. I

became the CIC/ECM Officer and DASH Intercept Controller on the KENNEDY from

FRAM Conversion (spring 1962) until June 1963.

Sometime in March or April of 1962, I was sent to DASH

Controller School, out on Long Island, at the GYRODYNE facility. What stands

out in my mind, is the bravery of the test pilot, Don Hollis, who was

sitting in the modified DASH Helicopter we learned to fly. If he had a full

head of hair, I’m sure it was white. I know we gave him a lifetime of

“pucker moments”. Yet, he didn't let any of us crash the bird in spite of

our lack of skill. I guess he had a big incentive, his life. This guy was my

hero.

We were trained to operate the DASH Helicopter from launch to

recovery from the hangar deck, as well as from CIC on attack missions.

However, my station was in CIC for the purpose of attacking submarines. Only

under an emergency would I launch and recover the weapon from the hangar

deck. There was another controller, the Deck Controller, for that task. Once

launched by the Deck Controller, the Intercept Controller in CIC took over.

After the mission, I would place the helicopter on station near the ship and

turn control over to the Deck Controller for the recovery. This was the man

with the real skill.

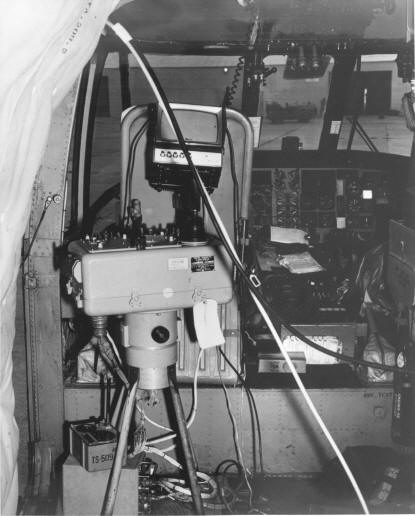

As far as the DASH set up in KENNEDY ’s CIC, you’ll have to

bear with the fuzziness of an old sailor’s memory. To begin with, I had to

be in a position to see the plotter clearly. As I recall, the controller was

placed on the after starboard corner of the NC2 plotter. The plotter was

near the port bulkhead. As the controller, I either faced forward toward the

door from the bridge and watched the plot to my left or faced the plotter

directly to port from the starboard side of the plotter. Each ship was

configured differently. During FRAM Conversion, the CIC and DASH teams had

the latitude, within reason, to set up CIC in a way that best suited the

team. Len Barrett, one of my Radarmen, might have a better memory on the

exact placement, since he spent a lot more time in that space than I did.

As a concept, the DASH weapons system was a great idea at the time. It gave

the destroyer stand off ability, surprise and devastating destructive power.

Although, when we operated the DASH Helicopter, it was always a moment of

great anxiety and excitement, wondering if we would ever get it back aboard

ship safely. Wonder of wonders, we did. However, there were fleet reports of

the bird ignoring instructions and happily flying away, over the horizon, on

the last vector it was given. I am happy to say, that never happened on the

Kennedy when I was a controller, thanks to the skills of the sailors on the

DASH team – both on the hanger deck and within CIC.

As a concept, the DASH weapons system was a great idea at the time. It gave

the destroyer stand off ability, surprise and devastating destructive power.

Although, when we operated the DASH Helicopter, it was always a moment of

great anxiety and excitement, wondering if we would ever get it back aboard

ship safely. Wonder of wonders, we did. However, there were fleet reports of

the bird ignoring instructions and happily flying away, over the horizon, on

the last vector it was given. I am happy to say, that never happened on the

Kennedy when I was a controller, thanks to the skills of the sailors on the

DASH team – both on the hanger deck and within CIC.

GITMO Cuba was our first port of call after FRAM Conversion

(late May or early June of 1962) – an eternity of shakedown, instrument

calibration and training. What a place to be in the middle of summer, living

under the hangar deck without air conditioning. After successfully passing

the Post FRAM Quals., we were dispatched to Newport, RI, nesting with our

squadron, DESRON 10 and our families. That fall, we left for the Cuban

Missile Crisis and took our station in the blockade. The KENNEDY was the

only US ship to board a Soviet chartered freighter during the conflict. Our

Captain was CDR. Nikolai Mikhalevski (sp.), who hailed the freighter, in

fluent Russian, to "heave to and prepare to take on boarders" We sent a

formal boarding party aboard, under the command of the XO in dress whites

replete with swords and small arms, to inspect for missiles and other

offensive hardware. We sent her on her way after finding her clean.

On our return to Newport, in December of 1962, we began

perfecting our ASROC and DASH skills in months of ASW training exercises in

the Atlantic until I left active duty in June 1963.

James B. Rucker, Jr.

DASH Controller,

USS JOSEPH P. KENNEDY JR. (DD-850)

November 5, 2004

|

|

|

Remembering DASH

It

was in 1963 that I completed the Tin Can Sailor's version of flight

training, and became the 14th officer qualified to pilot the QH-50C Drone

Anti-Submarine Helicopter. In classrooms at Dam Neck, Virginia, we learned

the basics of rotary wing flight. Out on the concrete pad at water's edge,

we first stood at the controls of this odd-looking bird - a kind of big,

leggy insect, with all the working parts on the outside. It

was in 1963 that I completed the Tin Can Sailor's version of flight

training, and became the 14th officer qualified to pilot the QH-50C Drone

Anti-Submarine Helicopter. In classrooms at Dam Neck, Virginia, we learned

the basics of rotary wing flight. Out on the concrete pad at water's edge,

we first stood at the controls of this odd-looking bird - a kind of big,

leggy insect, with all the working parts on the outside.

Following training, I reported aboard USS AULT (DD-698).

She'd completed FRAM conversion six months earlier. Her two little

helicopters came aboard in Norfolk, along with three experienced aviation

specialists who never thought they'd serve aboard such a small ship. We

assigned work benches and set up a coffee mess in the hangar. The crew, all

veterans of flattops, found it amusing that the coffee pot had to be secured

against heavy weather. Our two birds we affectionately named Flotsam and

Jetsam. It was now official. We were the 7th Operational

DASH Detachment.

Once at sea, we flew as often as we could. It was a pleasant

routine, rolling the bird out on deck, removing the wheels, tightening the

hold-down to a flush deck cleat, attaching the umbilicals. After getting

permission from the bridge, I'd crank up the 300 horsepower turbine. The

gradually rising pitch of the starter would lead to a satisfying,

deep-throated whomp as the engine ignited and then came up to speed. The

pre-flight check was brief. As my crew chief liked to say, "The two rotors

are going in opposite directions; she's good to go."

I recall that there was a momentary reluctance to pop the

umbilicals, knowing from that moment on we'd no longer be getting anything

other than visual data about how Flotsam or Jetsam was doing. The absence

of any telemetry meant you were flying blind, a seat-of-the pants kind of

operation with not an instrument in sight. In fact, it was partly that

barnstormer attitude that made it fun. I'd notify the bridge that we were

ready. If it were windy and we were operating independently, the OOD would

turn so we had the relative breeze on the port bow which meant less

turbulence from the hangar. I'd release the tie- down, dial in some

collective with my thumb, and we were airborne.

I enjoyed standing at that console, with its joy stick and

altitude knob. It would be more than 20 years before hand held video games

flooded the market, but back then I already had a sense of why the craze

would take hold. And from the beginning we did our best to show off our new

birds. We flew Flotsam near the USS ALBANY while SECNAV was on board. It

was his first look at a QH-50C. I enjoyed standing at that console, with its joy stick and

altitude knob. It would be more than 20 years before hand held video games

flooded the market, but back then I already had a sense of why the craze

would take hold. And from the beginning we did our best to show off our new

birds. We flew Flotsam near the USS ALBANY while SECNAV was on board. It

was his first look at a QH-50C.

We were often in company with the relatively new USS

ENTERPRISE (CVN-65), acting as her plane guard, being told to do our best

when she'd crank it on, well beyond our flank speed, and speed away over the

horizon. More than once, I flew along with her manned helicopters. Two of

her "angels" would assume positions astern of our bird, left and right. We

were careful to keep the maneuvers modest, making turns in small segments.

The pilots were impressed with her maneuverability and how sharply she could

come about. They seemed to like our little rascals, and there were

indications that collaboration and joint operations would be possible.

However, from the beginning I knew that we were the interlopers and needed

to defer to them.

Ours was the first DASH Detachment to deploy to the Med. On the day we

joined the carrier task group off Gibraltar, I was on the bridge. We sent

the Task Group commander a request to conduct flight operations. The flag

duty officer, certain that we had screwed up, quickly responded that we

should check the signal book. Destroyers do not usually ask for permission

to fly! We reaffirmed our request. There was a long pause. He must have

checked the op order where it listed our QH-50 capability. The request was

granted. Our first flight within the formation caused quite a stir. A

message of appreciation from the Sixth Fleet Commander was answered by our

captain, with some details about our detachment and, specifically, that our

birds were called Flotsam and Jetsam. On subsequent days, the admiral

would send greetings and ask which of the two birds was in operation.

On one

occasion, the USS ENTERPRISE paid a surprising tribute to us DD aviators.

We were in a screen position, conducting local DASH flight ops.

ENTERPRISE designated our ship as the guide and signaled she was changing

her position. Showing off her speed and maneuverability, she came

around and fell into place 1500 yards off our starboard quarter - in classic

plane guard position, the position we so often took on her. A couple

of her helos were in the air and documented it. It was a treat … an

imaginative and unusually gracious, modest, and accommodating gesture for

the Big “E.” On one

occasion, the USS ENTERPRISE paid a surprising tribute to us DD aviators.

We were in a screen position, conducting local DASH flight ops.

ENTERPRISE designated our ship as the guide and signaled she was changing

her position. Showing off her speed and maneuverability, she came

around and fell into place 1500 yards off our starboard quarter - in classic

plane guard position, the position we so often took on her. A couple

of her helos were in the air and documented it. It was a treat … an

imaginative and unusually gracious, modest, and accommodating gesture for

the Big “E.”

"Big E"

was, of course, pretty sure of itself. Particularly in its early days. When

a destroyer went along to re-fuel, the signalmen would send word to the

ship: “You are the 18th ship to refuel from the nuclear power Enterprise.

Congratulations.

As we started our approach, our skipper sent a message: “Congratulations;

You are the first nuclear powered-carrier to refuel the USS AULT.” He

pre-empted their message, and I think they were pissed off.

On the AULT we had great success with night flights, and I

found the birds relatively easy to land in heavy weather. My engineman was

a fireplug of a guy, adept at sliding across the wet and heaving deck to

quickly get a tie down chain on her as she touched down. All three of my

crew of specialists were outstanding, training the other members of our

detachment, keeping the birds flying, never losing a one.

We did some ship-to-ship transfers, using the QH-50. The

most memorable involved fresh doughnuts from our galley, made by one of our

very talented bakers. We were in company with other ships of our squadron

and made arrangements to maneuver close to the DD carrying the flag. We put

the doughnuts in a cardboard box, hung below our bird on a long string. We

took off, lifted the box clear of the deck, then translated our bird over

the other ship's fantail. Easing her down gradually, the box was caught by

a boatswain's mate who cut the string and handed the doughnuts to the

commodore. We described it in our log a defining and

historical moment in vertical replenishment. I know subsequent

detachments passed control to other ships, but since we were always the only

DASH ship, all the maneuvering was from our deck.

I recall only one really scary moment. I was flying in the

vicinity of the USS SARATOGA (CVA-60). It was a line of sight event, from

the flight deck, and I was maneuvering at about her flag bridge level. The

intention was to fly beyond, then circle around her, and then return. About

half way through the evolution, as Jetsam was about to disappear behind the

carrier's island, I realized that I had no real idea about the relative

distance of the carrier and my small bird. Was I on the far side of the

carrier, or not?

It was a great relief when the bird emerged from behind the

island, without making contact. We were never chastised on the radio for

flying too close, so perhaps my margin was good enough. Or maybe the

admiral thought I knew what I was doing, buzzing his bridge. As for me, I

said a prayer of gratitude and promised myself never to try such a thing

again. It was one of many experiences I had that reminded me of how often

our ships are right out there on the edge, led by enthusiastic -- but very

young -- men and women. Hard to imagine how any skipper sleeps at night.

Somewhere, I've got a record of the number of landings and amount of flight

time accrued during my year-long tour. During that time, we continued to

successfully exercise our birds. There are photos of the CO

and his DASH detachment, with a cake celebrating our 100th landing.

And in a cruise book, we have a picture of a cake with 500th

landing written in icing. They were good birds and the crew did a

fine job of keeping them operational.

Somewhere, I've got a record of the number of landings and amount of flight

time accrued during my year-long tour. During that time, we continued to

successfully exercise our birds. There are photos of the CO

and his DASH detachment, with a cake celebrating our 100th landing.

And in a cruise book, we have a picture of a cake with 500th

landing written in icing. They were good birds and the crew did a

fine job of keeping them operational.

After I left the navy and later learned that the QH-50's were

no longer in fleet use, I wondered how much of their demise was because of

turf wars - a reaction to the effrontery of a destroyerman claiming a place

in the aviator's skies. And that led me to wonder whether we should have

had aviators or aviation officers of some stripe, flying our Flotsams and

Jetsams. Maybe they would have worked out a longer or more peaceful

coexistence. In some areas I believe we're making progress in healing this

sort of breach. NASA, after very divisive times, is working to bring

robotics and manned flight - especially exploration -- into a joint effort.

The armed services are bound to eventually recognize the values of a

partnership, not a rivalry, between man and machine. Though star-crossed,

the QH-50's contributions and demonstrated practical value will continue to

help this effort.

During those early days of DASH, I sent in a number of proposals for

augmented mission capabilities, tactics, and additional onboard equipment.

The potential was enormous. Surveillance, target designation, communication

relay, search and rescue, critical parts transfer. The possible return on

such a small investment could have been significant, expanding the

destroyer's horizons, literally and figuratively. I never received a

response, but it was fun to be in at the beginning and to consider the kind

of options that would be exercised with gun fire support in Viet Nam. But

that’s another story.

All I

can say in closing is that flying the QH-50C was a treat.

Paul Morgan,

DASH officer and deck controller; Sept. 1963 to Sept. 1964

USS AULT (DD-698)

April 27, 2005 & BIG E photo added April 16, 2011

|

|

|

I looked at your website and am impressed. It is

really comprehensive.

I

served in two FRAM I destroyers. The first,

USS VOGELGESANG (DD-862),

was a LANTFLT ship engaged in ASW for much of my tour. I was the DCA but

due to conflicts in pipeline training and deployment schedules I found

myself controlling DASH too. Since DASH was a weapons department asset it

was rare to find a snipe with his hands on the controls. I was generally

stationed in CIC since the 1st Lt. favored the deck and he was

senior. We flew the “Charlie Bird” (QH-50C) when I first arrived in

January 1967 but transitioned to the “Delta” (QH-50D) soon thereafter. I

really enjoyed the “Delta” with its greater power and therefore payload.

Although the “C” could carry two MK-44’s you had to be careful on a warm

day. I remember Dave, (David Norton was the 1st Lt.) taking a

bird off with two torpedoes aboard and having it settle into the water

20ft off the ship’s starboard quarter. He reacted quickly and shifted

control to me in CIC because he could not release a weapon from the deck

station, I released one weapon and flew the bird free of the ship from

CIC. The old man nearly had a heart attack! I guess, like manned

aircraft pilots, nearly every DASH controller has a story of an exciting

event or two in his pocket. We sure had fun and in retrospect, we were

very good with the system. Our accuracy was at least as good as the ASROC

and we had the advantage of placing the weapon right in front of the

submarine. Unfortunately, we were only as good as our sensors and the

nukes were quickly reducing our sonar’s effectiveness to nothing. I

served in two FRAM I destroyers. The first,

USS VOGELGESANG (DD-862),

was a LANTFLT ship engaged in ASW for much of my tour. I was the DCA but

due to conflicts in pipeline training and deployment schedules I found

myself controlling DASH too. Since DASH was a weapons department asset it

was rare to find a snipe with his hands on the controls. I was generally

stationed in CIC since the 1st Lt. favored the deck and he was

senior. We flew the “Charlie Bird” (QH-50C) when I first arrived in

January 1967 but transitioned to the “Delta” (QH-50D) soon thereafter. I

really enjoyed the “Delta” with its greater power and therefore payload.

Although the “C” could carry two MK-44’s you had to be careful on a warm

day. I remember Dave, (David Norton was the 1st Lt.) taking a

bird off with two torpedoes aboard and having it settle into the water

20ft off the ship’s starboard quarter. He reacted quickly and shifted

control to me in CIC because he could not release a weapon from the deck

station, I released one weapon and flew the bird free of the ship from

CIC. The old man nearly had a heart attack! I guess, like manned

aircraft pilots, nearly every DASH controller has a story of an exciting

event or two in his pocket. We sure had fun and in retrospect, we were

very good with the system. Our accuracy was at least as good as the ASROC

and we had the advantage of placing the weapon right in front of the

submarine. Unfortunately, we were only as good as our sensors and the

nukes were quickly reducing our sonar’s effectiveness to nothing.

My second destroyer tour was as Weapons Officer in

USS FECHTELER

(DD870). Her DASH was removed before I reported in

April 1969.

As a go through my 30 years of accumulated “stuff” I’ll look for anything

you might find interesting. If I find it I’ll pass it along.

James W. Orvis

DASH deck controller; Jan. 1967 to March 1969

USS VOGELGESANG (DD-862)

May 14, 2006

|

|

|

I

read with interest the various web sites recounting recollections of the

DASH program. I served on the USS BRIDGET DE 1024 and the USS Piedmont AD-17

from about 1967 to 1968 with my responsibility being the ship board

electronics. The Bridget flew DASH on a very limited basis. I remember one

time where either the surface or air search radar were down on the ship, we

launched in a haze and the “bird” got very near it’s 10 nm range before

being picked up on radar. The CIC officer aimed it back toward the ship and

the captain got almost the entire crew out on deck to look for it as it

approached the ship. That flight came to a successful conclusion. I

read with interest the various web sites recounting recollections of the

DASH program. I served on the USS BRIDGET DE 1024 and the USS Piedmont AD-17

from about 1967 to 1968 with my responsibility being the ship board

electronics. The Bridget flew DASH on a very limited basis. I remember one

time where either the surface or air search radar were down on the ship, we

launched in a haze and the “bird” got very near it’s 10 nm range before

being picked up on radar. The CIC officer aimed it back toward the ship and

the captain got almost the entire crew out on deck to look for it as it

approached the ship. That flight came to a successful conclusion.

Just prior to my transfer to the Piedmont they flew a bird while enroute

from Subic Bay to Kaosiung probably in April or May of 1968. I did not

witness it but apparently it crashed after responding in exactly the

opposite direction to the stick commands that the flight deck pilot put in

on launch. I’m told the bird just missed a 30 foot whip antenna just forward

of the hangar, did a roll to the right and went into the ocean upside down.

As I recall, standard flight protocol always took the bird back over the

fantail. It had good floatation capabilities which deployed and they

recovered it. I saw it later and recall that the JP-5 fuel take had

apparently exploded because one end of the tank was blown out.

My recollection is that the wiring to the gyro was 3-phase [my description

and not technically correct] and I was quite sure that it would have been

impossible for them to have that wiring messed up such that it would respond

exactly 180 degrees opposite.

I remember the elevation problem associated with the training site on San

Clemente Island . I don’t remember the exact circumstances but saw one of

the officers in training fly a bird right into the west side of the island

with the altitude indicator at the [my recollection of his verbal report]

1,000 feet maximum for the QH-50.

My memories of DASH were all positive. In retrospect it seemed to me a very

creative approach to ASW that never fully realized it’s potential.

Richard Beach

ET USN

1964-1968

June 24, 2006

|

|

|

|

My name is Peter Berg and I was the

Dash Deck Officer aboard the USS John A. Bole (DD-755) from '65-'66. Bole

was homeported in San Diego. We are in the process of getting an officers

reunion together for May '07 and I found your the DASH website in doing some

homework to try to bring back some old memories.

I went through my DASH training on San Clemente island, CA. Our birds were

named Joann and Mary Ann (I think those were some girlfriends of the

previous DASH officer). My most memorable experience with DASH was similar

to one previously described by LTjg Joel Labow. We went through our

preflight procedures, turned up the bird, lifted off and WHAM the bird turns

180 degrees. As soon as it happened I knew what I did. I obviously did not

align the ships' gyro with the birds' gyro (a fundamental procedure). Now

the controls are 180 degrees out of sync. I push the stick left, the bird

goes right; move the stick right, the bird goes left; push the stick back

the bird comes forward; move the stick forward, the bird goes aft. Only the

altitude controls works as intended. Unlike Ltjg Labow I did not recall the

emergency realignment procedure (must have slept through that lesson). So I

informed the Captain on the bridge that we had a slight problem with our